FOOD TASTES BETTER AT SEA:

Dining Aboard the SS United States

Take a Seat | Setting the Table | What's on the Menu?

Innovation and Tech | Back of House | An Enduring Legacy

Guest Book | Shop

PREVIOUS: Innovation and Tech | NEXT: An Enduring Legacy

BACK OF HOUSE

Head Chef Otto Bismarck, Chefs, and Officers receive medals commemorating the 1952 Maiden Voyage. SS United States Conservancy Collection. Courtesy of Otto's son, Fred Bismarck.

National Maritime Union Membership Card from Kenneth Karlin. Kenneth sailed on the SS United States around age 17/18 a number of times, working as a Cabin Class waiter and First Class waiter. SS United States Conservancy Collection. Courtesy of Kenneth Karlin.

The Stewards' Department encompassed hundreds of crew in the kitchens, waiters in the dining rooms and lounges, and stewards who orchestrated hospitality.

Chief chef Otto Bismarck supervised the SS United States kitchen for the ship's entire service career. He directed over 176 chefs and kitchen crew members, who could prepare up to 9,000 meals a day. All non-officer seamen, except Pursers, were hired through the National Maritime Union (NMU) in Hiring Halls in New York. The NMU offered training for the Deck, Engine, and Stewards departments at their large, eleven-story Service and Educational Center on West 17th St in New York City.

The galleys, or kitchens, of the United States were the most racially and ethnically diverse parts of the ship, including many Black and Hispanic crew members. In 1954, out of the 134 Puerto Rican crew members aboard, over 85% of them worked in the kitchen. Only men were permitted to work in the kitchen. On the subject of women workers, Bismarck quipped to the New York Times, "We do not want them in the kitchen. They talk too much." Most crew were New York locals, coming from boroughs like the Bronx and Brooklyn. A number of kitchen crew were foreign citizens, mostly from Germany, but also England and Ireland.

Waiters and stewards hailed from across the country, including New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. The ranks of the 1st Class waiters were the most international, including many British men, as well as some from Germany and Spain. Most of the Cabin and Tourist Class waiters were American, with some from Germany. A small number of women served as stewardesses, delivering food to ladies' rooms, but never working in the restaurant spaces.

This headline comes from a US Lines publication, Sales News. This issue, No. 6, celebrates the "Blue Ribbon Crew of the Big U." SS United States Conservancy Collection. Courtesy of J. Meyer.

Browse this gallery of crew photos in the Conservancy’s collections. Many of these photos were donated by crew member’s families.

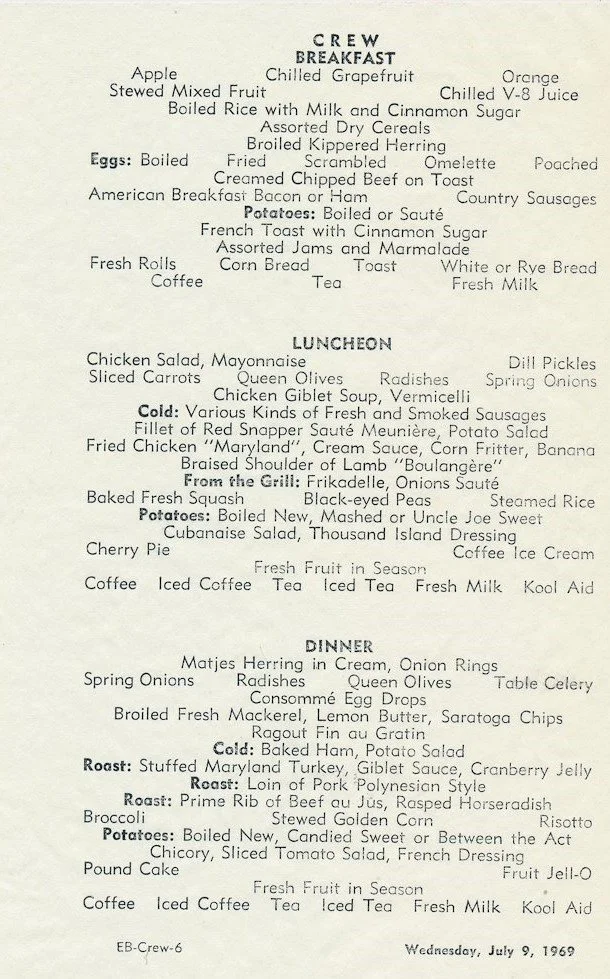

This crew menu from July 9, 1969, reveals the wide array of food offered to crew. The SS United States had a reputation for feeding her crew well compared to other ocean liners. Crew ate many of the same dishes offered to passengers. SS United States Conservancy Collection.

THE CREW EXPERIENCE

Food was prepared in the First and Cabin Class galley (A Deck), Tourist Class galley (A Deck), and the Steward's galley (B Deck). Positions ranged from Chef, Saucier, Soup Cook, Roast Cook, Potato Cook, Fish Cook, Kosher Chef, Butcher, Pantryman, Coffeeman, among many others.

Not all crew members had an easy time working in the fast paced, high energy kitchen. Dismissal reports reveal Bismarck's dislike for "lazy" workers who were "bad influences.” He demoted or fired others who were "incompetent" and could not perform in a "satisfactory manner."

Press outlets described him as a strict boss. A New York Times report described him thusly, "He stalks his galleys and serving pantries with an all seeing eye, insisting on perfection in preparation and presentation…” Bismarck's high standards were evident in the highly commended food.

When the kitchen closed, Bismarck blew his whistle to signal the crew to hose down all the surfaces. Before the cleaning could begin, the crew grabbed as many leftovers as they could. Though alcohol was strictly forbidden, drinking did happen. In the kitchen and pantry, this could lead to fights and a penalty of a day's wages, or even immediate dismissal.

Crew members ate in a number of mess rooms on B Deck, schedules and locations specific to their departments. For example, the deck and engine department had breakfast between 7:30AM - 8:30AM, whereas stewards ate breakfast between 6:30AM - 9AM.

“After closing the scullery, we would venture into the First Class galley and pick up a couple of filet mignons, some French bread, a number 10 can of draft beer, and take them back to the aft crew deck below the main deck and watch the seas roll by. Talk about the good life! At night we would gather in ‘Times Square,’ the crossroads of the crew quarters, and shoot the breeze…”

Sea Trials Stewards in Crew Galley, 1952. Photo Taken by Albert W. Durant. SS United States Conservancy Collection. Courtesy of Mariners’ Museum of Newport News, VA.

albert w. durant

Before the SS United States was declared fit for service, the ship was tested in top-secret speed trials in Virginia. One of the VIPs present during these trials was Albert W. Durant, a prominent Black photographer from Williamsburg, Virginia. He took over twenty-two black-and-white photographs of African-American kitchen staff, porters and restaurant captains. Durant's photos are the most comprehensive photos showing crew life on the SS United States. When so many photographs focused on passengers, Durant paid tribute to the hardworking crew who brought the ship to life.

These photographs were acquired by the SS United States Conservancy as part of a generous donation of over 600 artifacts from the ship made by the Mariners’ Museum of Newport News, VA, in 2016. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s John D. Rockefeller Library also owns a set of the images, and was the original source of the donation.

FOND MEMORIES

A testament to the hardworking crew, former passengers still remember their favorite waiters by name, and the kind deck stewards who cared for them when they were in the throes of seasickness. This "elite crew" was just as important as the fuel in making the SS United States succeed and emerge as the successful cultural icon she was.

Waiter Serving Joseph and Inga Borstler in 1967. SS United States Conservancy Collection. Courtesy of Harald Boerstler.

This 1964 photo shows the Stellmacher family and beloved waiter, Archie, in the background. SS United States Conservancy Collection. Courtesy of Linda Stellmacher-Lester.

From Barbara Franklin's 1957 or 1960 voyage. Left to right Josefine Joyce, John Joyce, Margaret Joyce, Barbara Joyce Franklin with Jimmy, their waiter. SS United States Conservancy Collection. Courtesy of Barbara Franklin.

“His name was Archie from Australia. When my mom was served a meal that had peas, she remarked ‘Oh, I get peas with this.’ Archie had a sense of humor and said ‘Yes. Mrs. Have a pea on me!’” ”

“I remember the staff and crew being very nice to me but especially the staff in the dining room who helped me decipher the menus. (I did not not speak English at the time.)”

“Walter, our server, we called the bumble bee because he hummed while serving.”

TIPPING

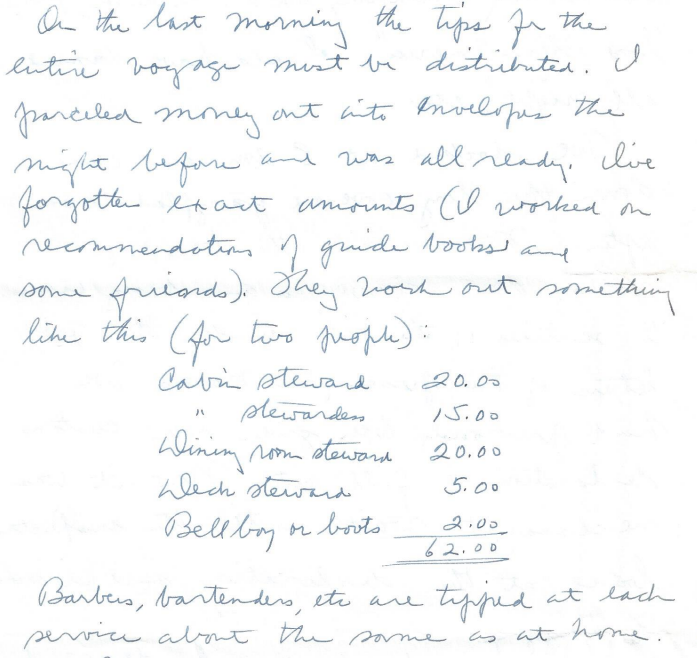

SS United States Conservancy Collection. Courtesy of William's granddaughter, Cathy Lindsley.

(From the diary of William S. Deeming, First Class passenger in the 1960s.)

“On the last morning the tips for the entire voyage must be distributed. I parceled money out into envelopes the night before and was all ready. I've forgotten exact amounts (I worked on recommendations of guide books and some friends). They work out something like this (for two people):

Cabin Steward 20.00

Cabin Stewardess 15.00

Dining Room

Steward 20.00

Deck Steward 05.00

Bellboy or boots 02.00

Total 62.00

Barbers, bartenders, etc are tipped at each service about the same as at home.”

Accounting for inflation, this would be equivalent to $629.45 in 2025.

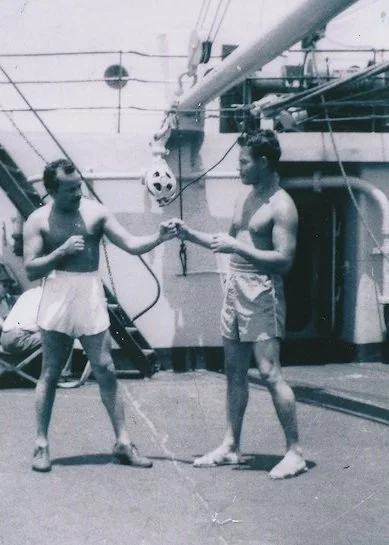

Miguel Cruz and his best friend Elviro 'Pepe' Sontiago. Miguel worked on the ship from July 21, 1953 to November 7, 1969.

SS United States Conservancy Collection. Courtesy of Miguel's daughter, Ruth Murphy.

CREW FOR LIFE

Working on the SS United States was not easy: it required long hours, specialized training, and dedication to efficiency. But by many crew's accounts, it was highly rewarding. It was an honor to be a part of the beloved ship; so much so, many crew members served on board for the ship's entire service career. One such seaman, Marcus Hemmington Tucker, worked his way up from Second Confectioner to Chief Cook, and eventually, Chief Steward. He also served as an NMU Patrolman for a number of years. Another long serving crew member, Miguel Cruz, worked for over sixteen years aboard in the galleys and pantries.

Crew members forged deep relationships with each other that lasted beyond the ship's service career. Following her retirement, crew reunions played an important role in preserving the ship's history.